Fireman Dylan Hutson

Conductor James Garcia

Fireman Dylan Hutson

Engineer Harry Haas

Engineer Jeff Stebbins & Engineer/fireman Carlos Llamas

Engineer Jeremy Garcia

Lady brakeman Laney Zook

Engineer Max Casias

Fireman Dylan Hutson

K-36 No. 488 charges out of Antonito, Colorado on the morning of October 9th, 2022.

Jet Age Hogger.

As two commercial airliners streak high across the skies above New Mexico, engineer Harry Haas sits at the controls of No. 488 in Chama.

484 and 488 charge up Cumbres Pass near Coxo in October 2022.

In the Jet Age.

K-27 No. 463 heads back to Antonito late on the afternoon of October 7th, 2022.

Fireman Dylan Hutson tends to the old kerosene classification lamps on No. 488. October 6th, 2022. Chama, NM.

Conductor James Garcia enjoys the view from the open gondola as the train heads out onto the San Luis Valley late on the afternoon of October 7th, 2022.

Fireman Dylan Hutson oils the bell on No. 488.

Engineer Harry Haas with his oil cans and No. 488.

Engineers Jeff Stebbins and Carlos Llamas at Osier, Colorado. August 2022.

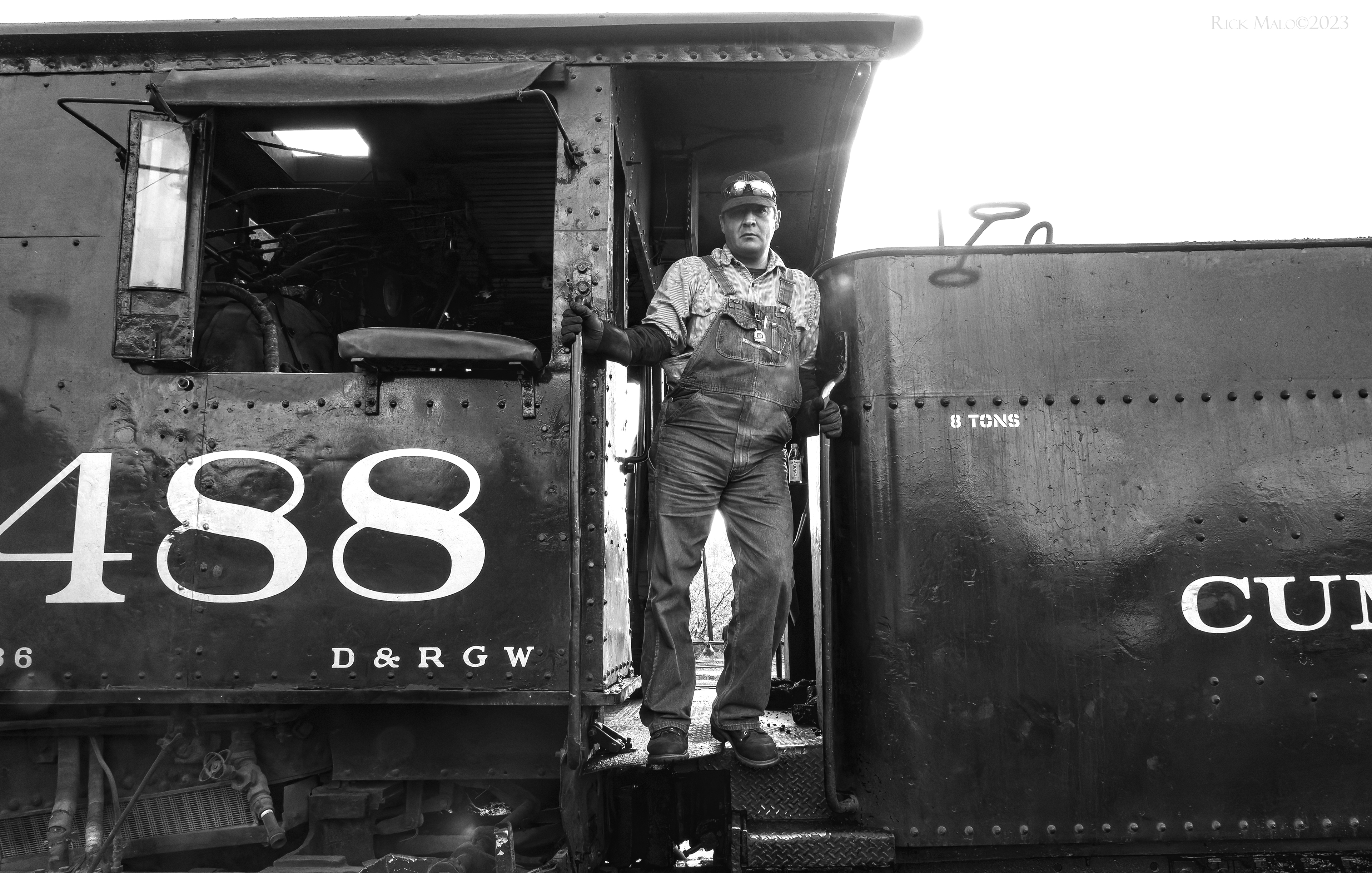

Engineer Jeremy Garcia strikes the classic pose in the gangway of No. 488 in Chama, NM.

Lady Brakeman Laney Zook.

Engineer Max Casias cleans the ashpan.

Dylan Hutson tops off the sand dome on No. 489 on the evening of October 5th, 2022.

The Last Boom.

A Mudhen with the San Juan at Antonito, Colorado.

Stepping across the decades at Chama.

With Mount San Antonio in the background, K-27 No. 463 rolls the morning train west into New Mexico.

A mix of eras rest at Antonito, Colorado.

Ten-Wheeler T-12 No. 168, built by Baldwin in 1883 as Denver & Rio Grande Class 47.

Mikado No. 484 built by Baldwin in 1925 as Denver & Rio Grande Western class K-36.

K-27 No. 463, built by Baldwin in 1903 as D&RG Class 125, rolls across the San Luis Valley on a cloudy August 2022 afternoon.

A young railfan watches as Carlos Llamas fills the tender tank of No. 463 at Sublette, Colorado. August 2022.

Saturday, October 8th, 2022 is double-header day, and railfans gather in the yard at Chama, New Mexico to watch the action.

With the aspen in full color on a gorgeous High Country Saturday morning, the double-header charges up the grade towards Cumbres Pass.